Is risk the next big thing?

In their paper, What doesn’t kill you will only make you more risk-loving: Early-life disasters and CEO behavior, Gennaro Bernile, Vineet Bhagwat, and P. Raghavendra Rau wrote that “CEOs who experience fatal disasters without extremely negative consequences lead firms that behave more aggressively, whereas CEOs who witness the extreme downside of disasters behave more conservatively.”

Interesting. And, I remember listening to an interview with Steve Jobs1 where he talked about such an experience – “I was walking across the grass at my schoolyard going home at about three in the afternoon when somebody yelled that the President had been shot and killed. I must have been about seven or eight years old, I guess, and I knew exactly what it meant. I also remember very much the Cuban Missile Crisis. I probably didn’t sleep for three or four nights because I was afraid that if I went to sleep I wouldn’t wake up. I guess I was seven years old at the time and I understood exactly what was going on. I think everybody did. It was really a terror that I will never forget, and it probably never really left. I think that everyone felt it at that time.”

I reached out to Mr. Rau, asking if he saw any correlation between COVID and future risk-taking CEOs. Here is his note back to me:

Not really, Kathy. Our paper examines formative influences on CEOs during a period of time when they are most receptive to these influences (i.e. between the ages of 5 and 15). Covid was a relatively short term unexpected disaster that had differential effects on different forms of companies in different locations. So I would not expect any casual influence from Covid on current CEOs. — Best, Raghu

While COVID isn’t the same kind of disaster the authors reference, I do believe COVID is generating plenty of current risk-taking CEOS.

Here’s why…

Think about risk in general. In fact, think about the opposite of risk.

The essence of a thing never comes into existence by itself and as itself alone. It always manifests itself along with and by means of its own opposite. – Novack, 1986

What’s the opposite of risk?

Safety

Secure

Certain

Protect

Invulnerability

Fixedness

Inaction

Firmness

Idleness

Immunity

Asylum

For many, COVID has wiped out or lessened much of the safety, security, certainty, protection, and invulnerability we had or thought we had.

So, do we have fixedness, inaction, firmness, idleness, immunity, and asylum?

Is fixedness, inaction, firmness, idleness, immunity, and asylum really the opposite of risk? Or, could you argue that every word on the opposite side is far riskier than risk?

Has America and the small businesses and corporations who drive it lost its mo?

Why don’t employees want to come back into the office? Is it really the fear of COVID, or could it be something else? Could they be unhappy? Could they be bored out of their minds? Could they be craving a change?

Maybe they’re secretly begging for transformation. Something new, better, more exciting to focus on.

Joseph Campbell said, “People say that what we’re all seeking is a meaning for life. I don’t think that’s what we’re really seeking. I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive, so that our life experience on the purely physical plane will have resonance within our innermost being and reality, so that we actually feel the rapture of being alive.”2

Is there a connection here? Are employees and companies looking for the experience of being alive?

I wonder, if companies were people, what would they say? What truths and confessions would they whisper in our ears?

Would the company’s original soul recognize itself anymore?

What about the people inside?

The 2015 Gallup poll3 found that 68% of employees are disengaged (United States). 68%…That’s a lot of uninterested people.

Are they just crappy employees? Or, is there just not that much to engage with at work? Is their interest wasted with too many mind-numbing activities that have no purpose? Are they set up for failure and boredom? Are they all in a vicious cycle and just exhausted?

To me, here’s an example of how the soul of a company can wither. It’s not as sexy as the absence of some insanely great purpose or an initiative to save the world, but it’s one of those things that can eat away at a person’s morale and enthusiasm for their work.

Example:

The company is an engineer-to-order company – a project environment.

They have a product development group that consists of six departments:

Product managers

Engineering

Engineering services

Industrialization

Production

Support services

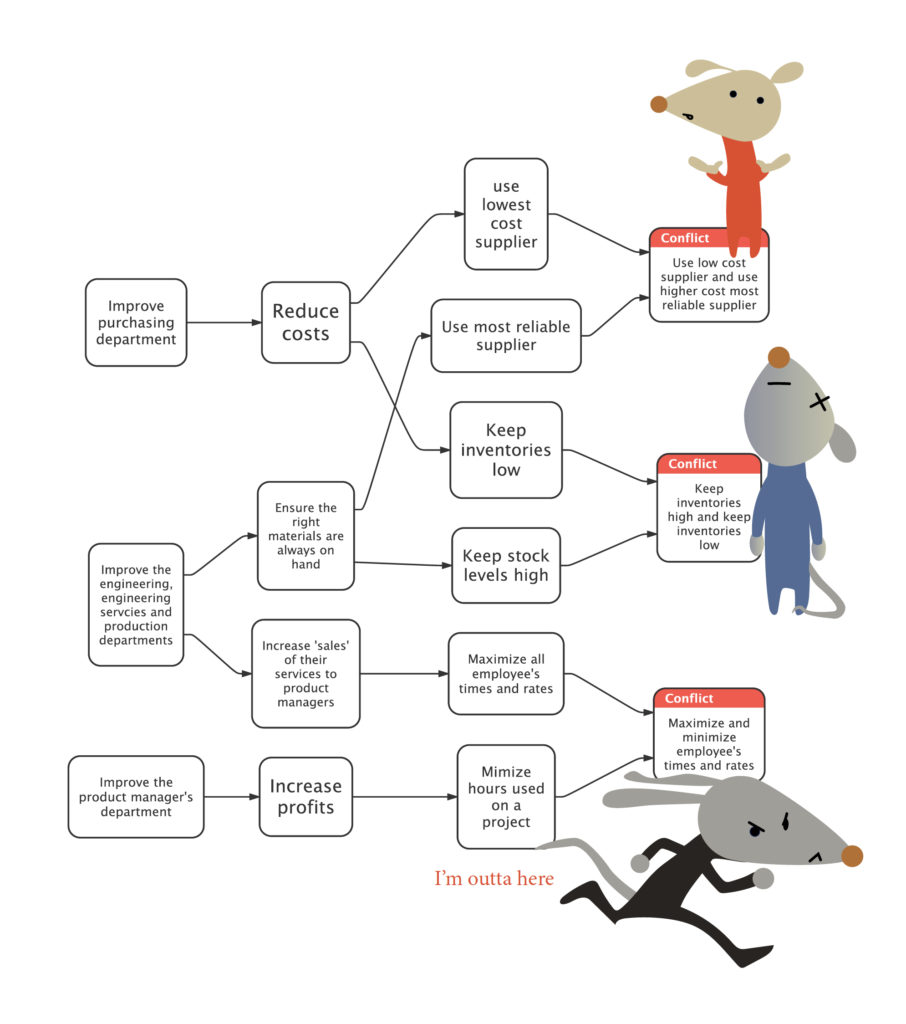

Product managers are measured on profit volume, milestones, and due dates. This department is run as a profit center where each department charges for their services. The way product managers are successful is to reserve resources to protect against uncertainty and minimize the hours used for a project – to improve profit.

Engineering, engineering services, and production are measured on the efficient use of employees or resources. The way they are successful is making sure all resources are always busy – maximizing the hourly rates they charge the product managers.

Production also is measured by having the right materials on hand. To do this, they are very careful to choose the most reliable suppliers and have enough stock on hand (maybe even a slight excess).

Support services such as procurement, IT, and human resources are measured on minimizing costs. And for procurement, keeping stocks low.

Here’s the position they are all in:

So, in this case, employees are asked to be fully engaged while – all simultaneously – they maximize and minimize employee’s time and rates, they keep inventories high and low, and they use low cost and higher cost suppliers.

The assumption here is that efficiencies and improvements in individual departments equal maximum efficiencies and improvements for the whole company (the sum of the parts equals the whole).

These sort of tug-and-war scenarios are more common than one might think.

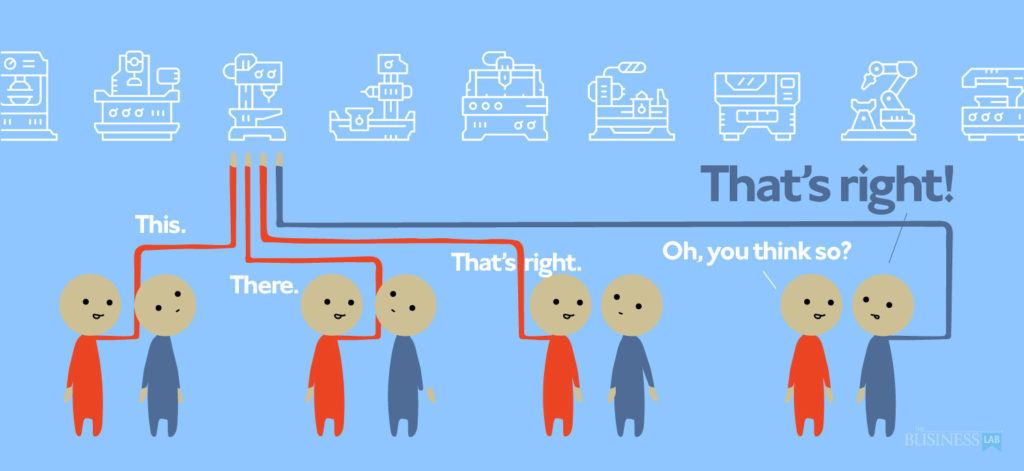

In manufacturing, employees are often measured on the ability to keep machines running as fast as possible as often as possible. So, when they have to stop a machine for a new setup, they are dinged for the reduction in machine time. This can mean they keep running more and more of what they already have set up. This leads to way too much of what isn’t needed, using raw materials that have been allocated to another order, and often delaying other orders. So, these employees are under pressure to simultaneously keep machines running and stop machines running. This also puts them in direct conflict with the sales and purchasing folks (if they ‘stole’ raw materials that didn’t belong to them).

The assumption here is idle machines equals waste, and waste is bad.

Speaking of sales, salespeople are often paid on commissions. The more they sell, the more they make. This often leads to them selling the wrong things – things that are easier to sell but far less profitable. They are under pressure to sell what’s profitable or sell what’s easier to sell and get paid faster.

The assumption here is that all products and services have the same value to the market and to the company selling them. The assumption may also be that the way products are priced and accounted for is helping profits.

In addition, salespeople are held directly responsible for almost all aspects of the sale – they are the ones management turns to when things go wrong (the deal doesn’t materialize, or the client is a slow pay). They are the ones responsible for communication between engineering and or manufacturing. They are the ones responsible for keeping the customer happy when things go wrong on their side. They are the ones that are often responsible for further qualifying the prospects and for prospecting in general. They are pressured to sell more stuff while simultaneously do all these other things. Research from InsideSales.com estimates salespeople spend only 37% of their time selling. This means the majority of the time, they are not selling.

Salespeople are asked to keep the company afloat by selling more while keeping management and customers happy by not selling.

The assumption here is that salespeople are solely responsible for the clients. Another assumption is that asking them to do other things gives management control. The particular measurement itself may make sense from the tried-and-true wisdom-nugget that ‘what gets measured, gets done.’

But that brings up the question – what do we want done? And, do we, or should we, all want the same thing done?

From the customer’s viewpoint – yeah, they want everyone focused on getting them what they bought and need. Their ‘done’ is the product or service promised.

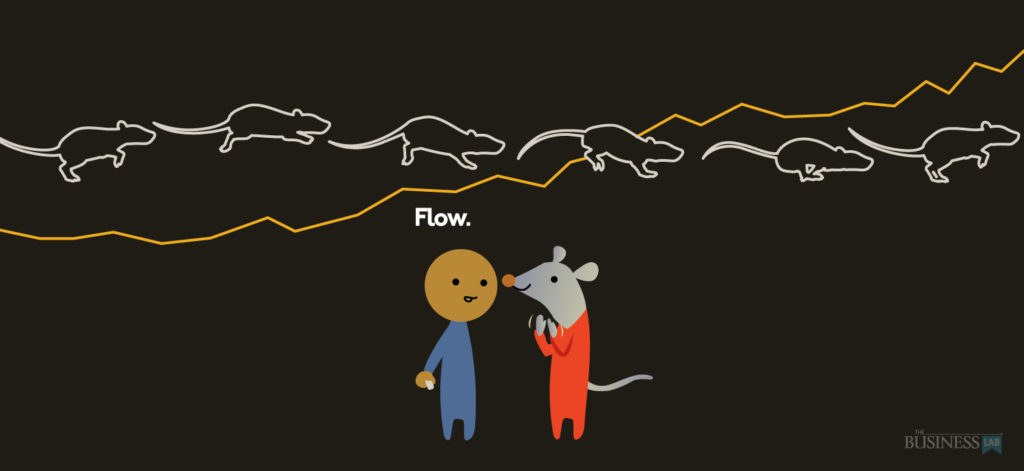

That brings up another tried-and-true wisdom-nugget goes something like – “the faster the flow, the more the dough.” This makes sense because it matches what the customers want – the product or service to flow to them as quickly as possible.

It would be interesting to see what would happen if a company tossed out its current measurements and tied all activity to flow.

Would that be risky? Would it be worthy enough to gain the engagement of most all employees?

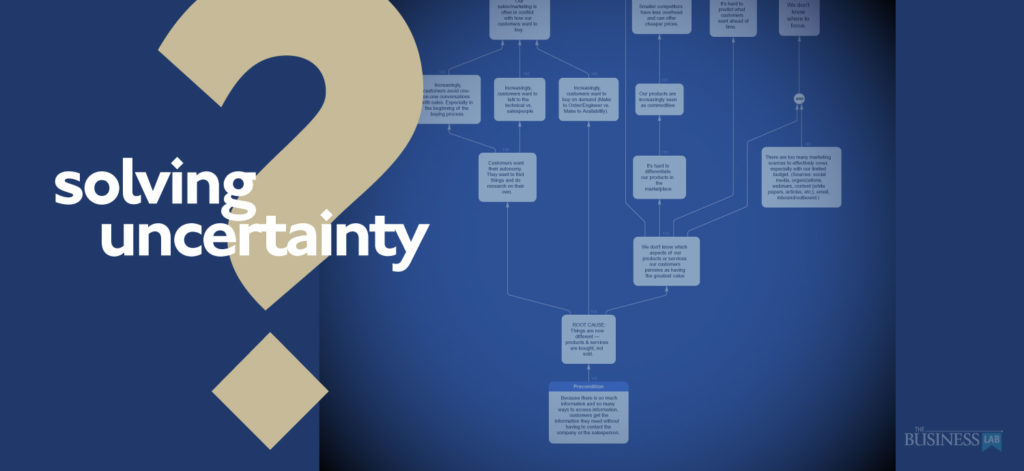

How risky would it be to conduct a significant assumption review, a cause-and-effect exercise to see if the hip bone really is connected to the backbone – or find out that it’s really connected to nothing the body needs or even wants.

It seems that eliminating some of the vicious cycles for employees could bring light back into their eyes. If nothing else, I’m sure they’d feel ‘heard and understood.’

It could be something to explore.

No, it’s not earth-shattering.

It’s pretty down-to-earth and can be tedious. But, we do know it does make a difference and helps get everyone focused on the health of the same body. If you need help building cause-and-effect maps, please buzz us at 281-610-8631.

Continued success,

Kathy

p.s. – Part Two focuses on the “higher (or at least more interesting) purpose” potential of risk.

1 — https://americanhistory.si.edu/comphist/sj1.html

2 — Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth will Bill Moyers

3 — https://news.gallup.com/poll/188144/employee-engagement-stagnant-2015.aspx